I’m a judge for Mass Challenge, as well as the Harvard Business School competition, and I’ve noticed that many entrepreneurs don’t know what market size means. Let me call out two of the most common mistakes, which can be the difference between recognizing a real opportunity and fooling yourself into believing something is an opportunity when it isn’t.

When a potential investor (including you, investing your time and career!) asks the size of your market, they’re asking how much money is out there (or how many customers) that could conceivable be spent on your company.

Market Size Isn’t Demographics

“The market for our new deodorant is anyone over the age of 12.” Actually, it isn’t. That’s way too general. Your market is defined at least in part by who you can reach. Your accessible market is what matters. You can’t reach everyone over the age of 12. “The market for our new deodorant is teenage girls between 14 and 18.” That is a much more realistic assessment and probably much more reachable through advertising in an identifiable set of magazines, TV ad spots, etc.

Market Size Isn’t Your Customer’s Revenues

The other big mistake entrepreneurs make is giving the market size as the total market revenues of all possible customers. “We sell hand sanitizers to media companies. Combined media revenues were $100 billion last year.” That’s a slippery evasion, because no media company will spend all their income on hand sanitizers. The market is not total revenues of all possible customers, but total amount all possible customers are likely to spend on your product. “Media companies spent $100 million on hand sanitizer last year, so that’s our market size.”

Market Size is the Potential Revenues You Can Reach

“The market for our internet-enabled back scratchers is middle-age men who feel the need for meaning in their lives. There are 50 million of them in my country, and at $19.95 (+ shipping and handling) that’s a billion dollar market.” Yes, except there’s no way to reach all 50 million of those customers. If there were a mailing list of all 50 million, you could do it. And you can certainly try your best to cover every possible advertising and media outlet that reaches middle-age men. But at the end of the day, only people you can reach with your message are potential customers.

An acquaintance of mine is developing a product for online gamers who make a living by livestreaming their games. That’s an addressable market, because there are forums, awards, conventions, podcasts, and an entire media ecosystem that pretty much every live streamer follows.

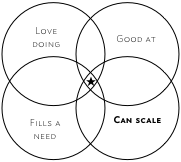

To put it all together:

When you’re evaluating the potential of an opportunity, be careful to ask how much money could reasonably come your way from the customers you’re explicitly able to reach. That is a much better number to use for market size.